A few days ago, a journalist friend of mine, Assed Baig, posted on Twitter to share a news report on Iran’s booming book trade. According to the report broadcast by Al-Jazeera, due to the stringency of international sanctions, European and American publishers are reluctant to deal with Iran. As Iranian publisher Mehdi Sojoudi Moghaddam put it, his irony deadpan, publishers in the West are reluctant to get involved with Iran thereby risking “selling millions of copies of their books.” And this means that in the absence of any international agreements, Iranian publishers enterprisingly step up to publish their own unauthorised translations of Western books.

I have long been interested in questions of translation, and how words, ideas and literature move between cultures. So I replied to Assed’s tweet, saying I’d be delighted if one day I discovered that any books of my own were translated into Persian, available in a bootlegged edition in the streets of Tehran. I’d take it as a win, I said.

A few moments later, somebody replied to say that actually one of them already had been: a small philosophy book I wrote several years ago on the subject of happiness.

The book was called A Practical Guide to Happiness: Think Deeply and Flourish, and was first published in 2012—almost a decade ago. It was republished in an updated edition in 2018 and has continued to sell pretty consistently ever since. But although the publishers, Icon Books had struck a couple of rights deals for foreign language editions, this was the first I’d heard of a version on the bookshelves in Iran.

Unexpected happiness (in Persian)

There was something incredibly exciting about the thought that my book could be available in Iran, in a hitherto unknown (at least to me) Persian edition. So I sent a message back. “I’d love to see a copy,” I said.

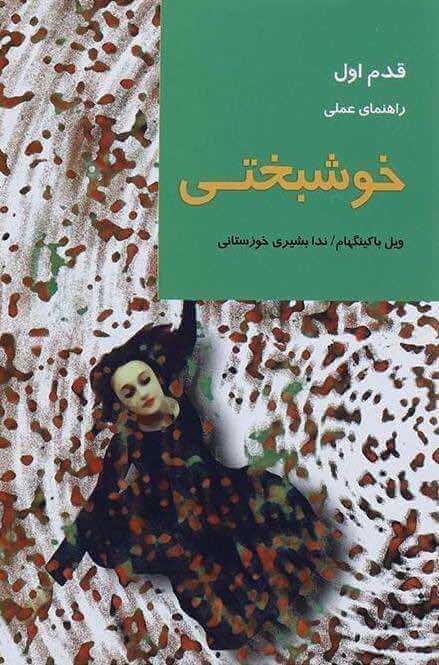

A few moments later, a Twitter user with a taste for sleuthing and a good command of Persian sent me a response with a picture of the book cover.

Given that I’m a writer who is doing their best to make a living from words, perhaps my first thought should have been one of annoyance. Here was an unauthorised edition, about which nobody had consulted either me or my publisher, and for which I had never been paid. But the moment I set eyes on the cover, I was filled with joy. It was a thing of beauty.

I don’t know Persian. But I made some attempts to study Urdu years ago, so I could navigate through the Persian script to pick out my name (ویل باکینگهام), alongside the name of the translator, Neda Bashiri Khuzestani (if you ever want to say hello, Neda, I’d be delighted to hear from you!). As for the cover image, it was wonderful. A woman held open her arms and lifted her head as if dancing ecstatically. Around her swirled red and green splotches that suggested a blizzard of rose petals. It had energy and life and movement.

I don’t know how the cover speaks to Iranian audiences. But it made me think of Sufism, with its rich philosophical and cultural traditions. And it made me regret that in the freewheeling mix of the original book—which took in a broad range of cultural references from Medieval Europe to ancient China, and from Buddhist India to contemporary positive psychology—I didn’t find space for including these traditions also. How great would it have been, I thought, to include a chapter on Al-Ghazālī’s The Alchemy of Happiness?

Somewhere in Tehran

But still—Al-Ghazālī’ or no Al-Ghazālī’—the book was out there, in a Persian edition. And stumbling over it felt like an unexpected gift.

Because what could be more wonderful than this? Someone, after all, had read the book and said to someone else, “Hey, let’s translate this one. I reckon people will like it.” Then they called up a translator and asked if she was available. The translator put in the time to translate the book. Someone else designed the cover, and someone prepared the final artwork. In this way, my little book written almost a decade ago had contributed in some small way to several people—my Iranian colleagues and peers whom I have never met—making a good, honest living.

And then somewhere in Tehran or Shiraz or Isfahan, perhaps even as I write this, somebody is picking up this bootlegged translation. And as they start to read, perhaps they agree, or perhaps they disagree. Or when they finish reading, maybe they pass the book on to a friend. Perhaps, half-way through, they leave it accidentally on a crowded bus. Or some throwaway line in the book—one that I hadn’t thought much about, but that was translated to give it more nuance than it ever had in the original—sparks off an idea, so they go off to write something of their own…

Because this is how words and books work. And of course, in a different world there would have been contracts, agreements, and royalties. But this is not the world we live in. Global politics are global politics, and while they remain so fraught and divisive, what could be more encouraging than the knowledge that, despite this divisiveness, all these kinds of rich, human connection still go on?

One day, if the climate of global politics shifts, it may be that there is an authorised version of this book. Who knows? Maybe I can add in a chapter on Al-Ghazālī… But until then, I am happy that even across all the disruptive forces of global politics, the real stuff of human connection—the passing back and forth of ideas, thoughts and stories, the stuff that really matters most—still goes on.

Image: Iranian miniature of a European priest carrying a book. Public domain via Wellcome Collection.

This piece was first published on Medium in 2021.