If philosophy has always been preoccupied with wisdom, its relationship with the opposite of wisdom—foolishness—has always been a vexed one. One reason for this is that throughout the history of philosophy, the relationship between wisdom and foolishness has not been one of simple opposition. Instead, it seems that for some philosophers, at least, there is a kind of wisdom in foolishness.

We already know that Socrates was a self-confessed know-nothing. And also we know that for the Zhuangzi there is something wise in giving up in the pursuit of wisdom. So when thinking through what it means to be wise, we are going to have to ask what it means to be foolish.

Looking for the light: The wise fool and the lamp

The idea of the Wise Fool has a long history. This history goes back at least as far as Socrates. Arguably, Socrates was both a fool (he was ignorant) and wise (he knew he was ignorant). Being both wise and a fool, he was able to fool with those who claimed wisdom for themselves, and in fooling with them, he could demonstrate that they too were fools — only more foolish fools than he was himself.

The Wise Fool is someone who, in their search for wisdom, appears foolish in the eyes of the world. In the ancient Greek world, the philosopher Diogenes the Cynic was even more well-known than Socrates for his foolish wisdom. In one famous story about Diogenes,

Plato defined Man as a featherless biped. The definition was generally well received. But Diogenes refuted it by plucking a chicken, bringing it to Plato’s Academy, plopping it down and proclaiming, ‘There’s Plato’s Man for you!’ [1]

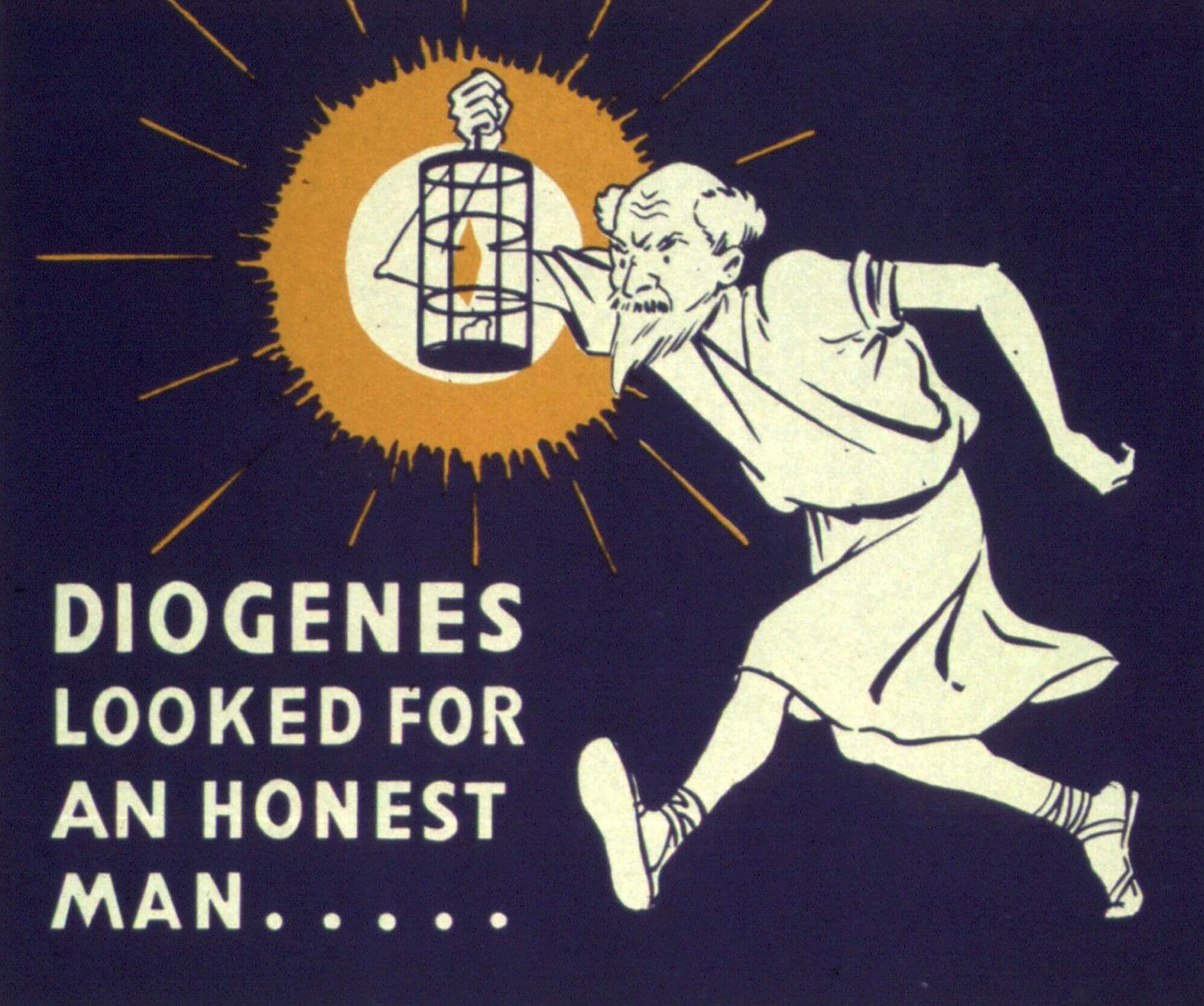

Plato was, unsurprisingly, not impressed by Diogenes. He allegedly described him as ‘Socrates with a screw loose.’ [2] And Diogenes’s behaviour was admittedly bizarre. Another much-retold anecdote is that he went around in full daylight holding up a lamp. When people asked him what he was doing, he said, ‘I’m searching for an honest man.’ [3]

Diogenes was a philosopher who mixed extravagant showmanship with a taste for ribald comedy. And he had a sharp awareness of the foolishness of everyday life. Plato’s description was apt: like Socrates, Diogenes called his fellow-citizens to account; but the ways in which he did so were more extreme. He was renowned, for example, for public masturbation. When challenged about his behaviour, he said, ‘If only rubbing the stomach could alleviate hunger pains so easily.’ [4]

Diogenes parading with his lamp through Athens is itself a kind of performance: he shows himself to be a fool (who needs a lamp in daylight?); but in making a scene like this, he is also underlining the fact there is nobody in the whole city who is a straight-up, honest human being.

This idea of the Wise Fool and their lamp recurred throughout the literary and philosophical traditions of Europe, and also spread beyond to the Islamic world. It appears in Aesop’s Fables, where Aesop himself is the fool with a lamp. Although as a historical figure Aesop predated Diogenes, many of the stories in the Fables are later attributions, and so it is likely that the story of Aesop is based on the story of Diogenes, and not vice versa.

Once when Aesop happened to be the only slave in his master’s household, he was ordered to prepare dinner earlier than usual. He thus had to visit a few houses looking for fire, until at last he found a place where he could light his lamp. Since his search had taken him out of his way along a winding path, he decided to shorten his journey on the way back and go straight through the forum. There amidst the crowds a talkative fellow shouted at him, ‘Aesop, what are you doing with a lamp in the middle of the day?’ ‘I’m just looking to see if I can find a real man’, said Aesop, as he quickly made his way back home. [5]

Echoes of this story appear again in the Islamic world. In traditions of Islamic storytelling, the exemplary Wise Fool is the Mullah Nasreddin. Nasreddin is a hard figure to pin down historically. Some accounts say he was Turkish and lived in the 13th century. Others say he was from Iraq and lived four centuries earlier. Still other accounts say he was from Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan, or Iran. But whether or not there was a historical model for Nasreddin, the stories are remarkably consistent. In these tales, Nasreddin alternates, ‘between the wise man and the fool, the wit and the numbskull.’ [6]

Two stories about Nasreddin and lamps seem to owe something to the tale of Diogenes. Here is the first:

‘I can see in the dark,’ boasted Nasreddin one day in the teahouse. ‘If that is so, why do we sometimes see you carrying a light through the streets?’ ‘Only to prevent other people from colliding with me.’ [7]

And here is the second, which is more well-known, and is the kind of story you get told at annoying training events.

Someone saw Nasreddin searching for something on the ground. ‘What have you lost, Mulla ?’ he asked. ‘My key,’ said the Mulla. So they both went down on their knees and looked for it. After a time the other man asked: ‘Where exactly did you drop it ?’ ‘In my own house.’ ‘Then why are you looking here?’ ‘There is more light here than inside my own house.’ [8]

These stories may or may not be the heirs of the tales about Diogenes, but in repeating the trope of the Wise Fool and their lamp, they seem to owe something to the Greek tale. A more direct borrowing is found in volume five of the Masnavi of the 13th century Sufi mystic Jalāl ad-Dīn Muhammad Rūmī, better known simply as Rumi. In Rumi’s tale, a Christian saint appears in the marketplace with a burning lamp.

That person was going about in a bazaar in the daytime with a candle, his heart full of love and (spiritual) ardour. A busybody said to him, ‘Hey, O such-and-such, what are you seeking beside every shop? Hey, why are you going about in search (of something) with a lamp in bright daylight? What is the joke?’ [9]

The mystic responds with a strange series of images. He says that his questioner is preoccupied only with the foam on the surface of things, and so he misses the significance of the sea. And he says that only when we can see beyond the foam of surface appearances is it possible to grasp hold of the deeper truths beneath, and free ourselves from hypocrisy.

He that regards the foam-flakes is (engaged) in reckoning (and calculation), while he that regards the Sea is without (conscious) volition.

He that regards the foam is in (continual) movement, while he that regards the Sea is devoid of hypocrisy. [10]

The madness of the philosophers

The idea that wisdom might look like folly, at least from some points of view, is one that goes back to Plato’s famous allegory of the cave in the Republic. In this allegory, Socrates asks us to imagine the mass of humankind like prisoners chained up in a cave, a fire blazing behind them. Between the prisoners and the fire pass a shadowy bunch of puppeteers. These puppeteers carry models of things like ducks and cows and tables and jumbo jets. The prisoners see the flickering shadows of the puppets on the wall, and they think, ‘Look, a duck! A cow! A table! A chair! A jumbo jet!’ And they take these flickering shadows for the whole of reality.

But then one day, one of the prisoners is released and forced out of the cave into the sunlight. There they see reality in all its unadorned richness. They see real ducks and cows. They see tables and chairs. Jumbo jets pass overhead. Reality is so much more than they had imagined. Before they only saw shadows of models of real things. Now they see the things themselves.

So, moved by compassion for their former prison-mates, they hurry back down to the cave to tell them. But once they get there, as they babble about the things they have seen, their former companions just look at them in bewilderment. What is this strange person talking about? Their stories of the world outside the cave invite ridicule, even the possibility of violence. Wouldn’t the prisoners think that their recently-returned companions were mad, Socrates asks, and put them to death (just as Socrates himself was to suffer a violent death of his own)?

The allegory of the cave is a complicated one (and will be the subject of a forthcoming Philosopher File. But it brings home a paradox baked into the heart of certain ideas of wisdom. If wisdom is seen as something remote and inaccessible, something radically different from the usual way of seeing the world, then in the eyes of the world, wisdom will look pretty strange, perhaps even indistinguishable from madness. To the wise, everyday life might look like madness; but to those of us stumbling through our everyday lives, wisdom may look equally mad. It was a point made by the Renaissance writer, Erasmus, in his In Praise of Folly:

And so it ordinarily fares with men as it fared in Plato’s myth, I gather, between those who admired shadows, still bound in the cave, and that one who broke away and, returning to the doorway, proclaimed that he had seen realities and that they who believed nothing existed except shadows were greatly deceived. Just as this wise man pitied and deplored the madness of those who were gripped by such an error, they, on their side, derided him as if he were raving, and cast him out.[11]

On Moral Fools

In Plato’s dialogues, Socrates is sometimes referred to as atopos, literally ‘out of place.’ He is strange and hard to place. And this strangeness was shared by many ancient Greek philosophers. As the French philosopher Pierre Hadot writes, in the Greek world, it was taken as read that philosophers are often awkward cases. They don’t fit in. Their ‘mode of being and living’ corresponds to a different vision from that of the mainstream. But while living in this radically different way, for the philosophers looking back at daily life, this life ‘must necessarily appear abnormal, like a state of madness, unconsciousness, and ignorance of reality.’[12]

These days, few philosophers would go quite this far. And even fewer have the sheer performative panache of Diogenes. The idea that philosophy might lead us to apparent foolishness is not necessarily a popular one among contemporary philosophers. Nevertheless, some contemporary philosophers have continued to argue that there is a kind of wisdom to be found in foolishness.

One recent example is the philosopher Hans-Georg Moeller. In his book The Moral Fool, he draws on the philosophical traditions of Daoism and Zen Buddhism to argue that our moral hang-ups work to our individual and collective detriment.

Moeller points out there a lack of any correlation between the amount of moral communication there is in a society, and how functional (or dysfunctional) that society is:

It is not the case that a relative lack of moral communication is correlated with a society in relative disorder or that a surge in moral communication is correlated with a society in relative peace. I also do not see how an increase in moral communication has ever made the world, or a person, in any empirical sense ‘better.’ [13]

In fact, the reverse if often true: wars and conflicts do correlate with high doses of moral communication. It is hard to justify a war in anything other than moral terms. So Moeller proposes that we might be better off owning up to the fact that we are moral fools, and that we don’t really know what we’re up to when it comes to ethics.

The consequence, Moeller suggests, is what could be called a quiet de-escalation of ethics as we embrace our own moral foolishness. The moral fool is not, Moeller says, an ’ethical anti-hero.’ Instead, the moral fool is ‘a more modest fellow’ who simply doesn’t know if the moral perspective is necessarily good, and so is averse to making moral judgements. The moral fool is nobody special: they are just somebody who has made peace with their moral foolishness.

In one respect, Moeller’s moral fool is like Socrates. This strange and unexemplary character admits, as did Socrates, to not knowing what virtue is (and in this sense, we are all sometimes Moral Fools). But then the moral fool goes beyond Socrates. Because Socrates, in coming to this conclusion, redoubles his search for virtue. Meanwhile, the moral fool, knowing that virtue causes all kinds of problems, simply gives up on the search. And having given up, the moral fool wanders off in their own sweet, purposeless foolish way. In this, perhaps, there is wisdom of a sort…

Discussion questions

- This time, you can see an old argument that wisdom involves a radical change of value-system. So from the point of view of ordinary people, philosophers (who are wise) will appear mad. And from the point of view of philosophers (who are, allegedly, wise), ordinary people will appear mad. But is the split really that stark? Must philosophers always be atopos?

- Are there any dangers to seeing wisdom, or those who possess it, as atopos, or somehow ‘out of place’? If so, what are these dangers?

- Have you ever experienced anything that, at first glance, appears to be utterly foolish, but on closer inspection seems to be remarkably wise?

- For Moeller, the moral fool is somebody who embraces their moral foolishness, and gives up on the quest for moral certainty. If we were all to become moral fools, how would the world change? Would it be better? Or would it be worse?

Notes

[1] Robert Dobbin, The Cynic Philosophers from Diogenes to Julian (Penguin Books 2012), p. 40.

[2] ibid. p. 40

[3] ibid. p. 40

[4] ibid. p. 46

[5] Aesop’s Fables, translated Laura Gibbs (Oxford University Press p. 171)

[6] See Necmi Erdogan, “Nasredin Hoca and Tamerlane: Encounters with Power in the Turkish Folk Traditions of Laughter” in Journal of Ethnography and Folklore 1(2), 2013, pp. 21-36

[7] Idries Shah, The Pleasantries of the Incredible Mulla Nasrudin ( Penguin Books 1968), p. 16.

[8] Idries Shaha, The Exploits of the Incomparable Mulla Nasrudin (Octagon Press 1988), p. 9

[9] Reza Nazari Saadi et. al., Masnawi: In Farsi with English Translation Volume 5 (Learn Persian Online 2018), p. 444

[10] ibid. p. 446

[11] In Praise of Folly by Desiderius Erasmus, translated by Hoyt Hopewell Hudson (Princeton University Press 2015), p. 46

[12] Pierre Hadot (translated Arnold I. Davidson), Philosophy as a Way of Life: Spiritual Exercises from Socrates to Foucault (Blackwell 1995), p. 58

[13] Hans-Georg Moeller, The Moral Fool (Columbia University Press 2009), p. 144

More further reading

Books

Try Sandra Billington’s A Social History of the Fool (Faber & Faber 2015).

Online resources

There’s an interview with Moeller about the Moral Fool on the Cambridge University Press blog.

Pierre Hadot is a fascinating philosopher. The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy has a good article on him. Read it here.

Image: Poster for Gentry Bros. circus. c. 1920-1940. Public domain via Library of Congress.