Taking your father to court

The philosopher Socrates is outside the court in Athens. He has been accused of impiety and corrupting the minds of the youth of the city—a charge for which he will soon be executed. As he is idling in the street outside the courthouse, he comes across an earnest young man called Euthyphro. The young man is bringing a charge of murder against his father, something that is all but unthinkable in Athenian society.

The substance of the charge is this. A servant who worked for Euthyphro’s father got drunk, and in a fit of anger killed one of the household slaves. Euthyphro’s dad took the servant, bound him hand and foot and threw him in a ditch while he decided what to do with him next. Unfortunately, before he could come to a decision, the servant died of hunger.

Socrates is shocked that Euthyphro is taking his father to court. But Euthyphro defends himself as follows:

It is ridiculous, Socrates, for you to think that it makes any difference whether the victim is a stranger or a relative. One should only watch whether the killer acted justly or not; if he acted justly, let him go, but if not, one should prosecute… [1]

Euthyphro argues that taking his father to court is the good and pious thing to do, even though under Athenian law only the relatives of the dead can press murder charges. Socrates, who is himself being accused of impiety, seizes on Euthyphro’s argument about the universality of justice and gets into a long wrangle with the young man about the nature of piety and goodness and justice, tying Euthyphro up in knots.

Plato’s dialogue is fascinating for a multitude of reasons. But the central tension with which it begins is one that is with us to this day: what happens when we encounter a conflict between our personal affiliations and loves, and the impersonal demands of justice?

Last week, we saw how we are evolved to live in small face-to-face societies. And for human beings living in groups like this, most interpersonal relationships can be negotiated on an ad hoc basis. But when scale things up, then things get more complicated. Then a tension opens up between the affiliations we have with those closest to us, and the demands of living in society with people most of whom are strangers.

Gong and the missing sheep

There’s an even starker version of the problem faced by Euthyphro and Socrates in the Analects of Confucius.

The Duke of She said to Confucius, “Among my people there is one we call ‘Upright Gong.’ When his father stole a sheep, he reported him to the authorities.”

Confucius replied, “Among my people, those who we consider ‘upright’ are different from this: fathers cover up for their sons, and sons cover up for their fathers. ‘Uprightness’ is to be found in this.”[2]

For Confucius, the demand that fathers should “cover up” for their sons, and vice versa (the Chinese word yin literally means “to hide” or “to conceal”) is a crucial component of the virtue usually known as filial piety (xiao in Chinese). It’s worth taking a moment to see what Confucius is and isn’t saying here. He is not saying that the father should not be charged with the crime of stealing a sheep. He is saying that it shouldn’t be his son who reports him to the authorities.

One way of understanding this is in terms of a tension between two kinds of “uprightness” (or, in Chinese, zhi). On the one hand, there is an uprightness to taking the law seriously. But on the other hand, there is an uprightness to observing the proper relationships with those who are close to you. Of course, we might say, we should obey the law. That is the upright thing to do. And of course, we should also do our best to protect the interests of those to whom we are closest. That too is the upright thing to do. But what happens when these two forms of uprightness come into conflict?

But is Confucius really saying we should let those who are close to us get away with anything, simply because they are close to us? This is a reading of the passage that sits awkwardly with Confucius’s other teachings. However, there is another reading. In this reading, Confucius recognises that when it comes to strangers or those with whom we don’t have personal bonds, it may be appropriate to resort to the law when we encounter wrongdoing. But when it comes to our intimates and those we are personally connected with, when we encounter wrongdoing, our first port of call shouldn’t be impersonal law. Instead, we should resort to other methods to help bring our wayward relatives in line.

Sometimes people think about Confucian filial piety as being exclusively about obedience. But the scholar Yong Huang points out that a crucial component of filial piety is remonstration. An example is in the following passage from the Family Sayings of Confucius or Kongzi Jiayu.

In ancient times, when a good king of a big state has seven ministers who dare to remonstrate, the king will not make mistakes; if a middle sized state has five remonstrating ministers, the state will have no danger; if a small state has three remonstrating ministers, the official salaries and positions can last. If a father has a remonstrating child, he will not fall into doing things without propriety; and if a scholar has a remonstrating friend, he will not do immoral things. So how can a son who merely obeys the parents be regarded as being filial, and a minister who merely obeys the ruler be regarded as being loyal? To be filial and loyal is to examine what to follow. [3]

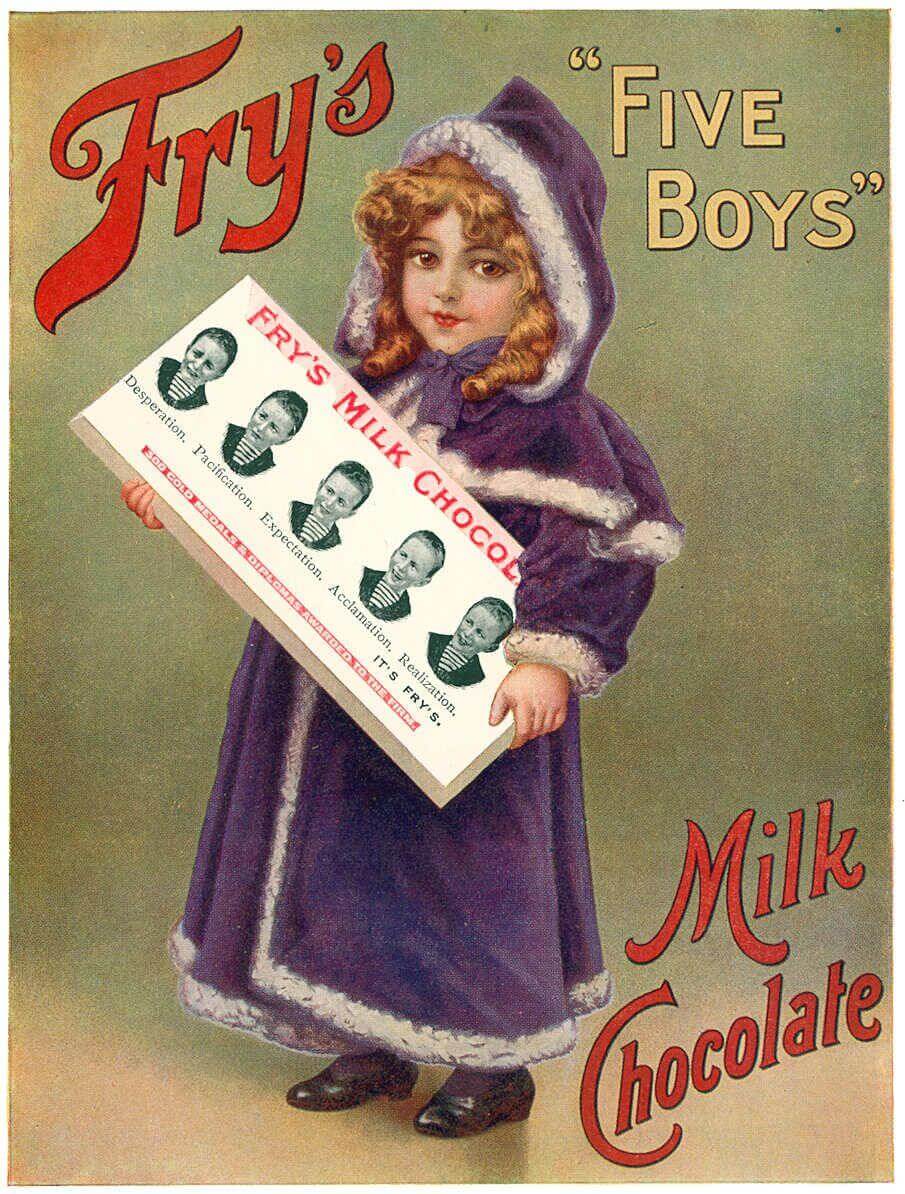

When it comes to a serious transgression—murder, for example—we may disagree that remonstration is the best first option. But for more minor transgressions, this goes with our instincts. If your child (or parent) stole a bar of chocolate from the small shop around the corner, it would be weird to immediately resort to impersonal justice as a way to right this wrong, and to drive them to the nearest police station. Instead, our instincts are probably that the right thing to do is to remonstrate with them, point out that stealing chocolate is probably not the best thing to do, and persuade them to take the chocolate back to the shop.

The challenge of universal love

For Confucius, it is entirely right that we respond differently to those who are closest to us. For each of us, our intimates form a circle of care and specific moral concern. And this is consistent with the idea of Dunbar’s number that we explored in last week’s article: the idea that human beings are adapted to keep track of a small handful of close intimates.

As a way of ordering society, this makes sense. We can’t care for everyone’s grandmother. But we might hope to live in a society where everybody cares for their own grandmother. You could see this Confucian view of society as an affiliation of interlocking units, each of these units bound by a sense of the proper relationships of care and moral concern. If this system worked as it should, then the need for laws and punishments, Confucius believed, would be minimal or even non-existent. If rulers set the right moral tone for their subjects, and their ministers held them morally to account, if parents set the right moral tone for their children, and their children held them to account, the society would function well.

But not everyone in ancient China agreed. The philosopher Mozi, who flourished around 430 BCE, was concerned that the partiality at the heart of Confucian ethics could too easily lead to self-interest and disorder. Instead, he argued in favour of what he called jian ai, or “universal love.” For Mozi and his followers (known as Mohists), universal love requires that we should respond equally and impartially to all other, regardless of the closeness of our connection. Confucian moral concern, the Mohists claimed, is blinkered and narrow.

Mozi’s starting point for his argument is that human societies fall into disorder because of a lack of love. The reason that you go out in the first place to steal that chocolate bar, or to steal that sheep, is a lack of love. You have not fully taken on board the interests of the sheep-owner, or the shop-owner. Acts like this are a failure of imagination, but they are also a failure of love. If you have sufficient love for others, this means you are unwilling to disadvantage them for your own advantage.

This is how Mozi makes his argument:

A sage, in taking the ordering of the world to be his business, must examine what disorder arises from. In his attempts, what does he discover disorder to arise from? It arises from lack of mutual love… Even if we come to those who are thieves and robbers in the world the same applies insofar as they love their own household but do not love the households of others. Therefore, they plunder other households in order to benefit their own households. A robber loves himself but not others. Therefore he robs others in order to benefit himself. How is this? In all cases it arises through want of mutual love. [4]

What Mozi calls love is the ability to take others’ interests into account, and to see these interests as having equal weight with our own interests and the interests of those close to us. Mozi’s jian ai is, in many ways, about justice, about how to manage the competing interests of different members of society. But the fact that Mozi talks about love suggests that this is more than just an intellectual principle of balancing out our interests against the interests of others. Instead, it is the idea that it is possible for us to have a feelingful and meaningful connection with the interests of those outside our narrow circle.

What society depends on

The problem with Mozi’s demand for universal love is, as Mozi himself admits, that it is very difficult. And one thing that makes it difficult, as we saw in the previous piece, is that we are not really equipped to cope with more than a small circle of one hundred and fifty others.

And this fact reminds us that in one sense, the rift between Mohism and Cofucianism is not as large as it might at first seem. The Mohists and the Confucians both know that we are partial, and that our concerns are partial. And they are both aware that broader systems of moral norms are important for a well-functioning society. What they differ on, above all else, is whether we should struggle to overcome our partiality, and what role law should play in our societies.

For the Mohists, if we want our societies to function well, it is important to manage our tendencies to partiality, and to put in place policies that encourage all those who live in that society to extend out the circle of their caring. And here we come to a surprising aspect of the disagreement between the Confucians and the Mohists. For Confucius, if our tendency for partial love is well-regulated by virtue and ritual, there is little need for legal systems of reward and punishment: our natural moral concern for those we love is all that we need for a well-functioning society. In the Analects, Confucius claims that:

If you try to guide the common people with coercive regulations and keep them in line with punishments, the common people will become evasive and will have no sense of shame. If, however, you guide them with virtue, and keep them in line by means of ritual, the people will have a sense of shame and will rectify themselves. [5]

There is an argument here that the ideal for Confucius is a kind of anarchism, but an anarchism of a weird kind. In this Confucian anarchist model, the system recognises multiple hierarchies. But the connections we have with each other are regulated by custom, ritual and virtue, rather than by law.

But for the Mohists, this idea is fanciful. No society has ever functioned like this. So if we want to encourage universal love, we need strict laws in place to police it:

Now things like universal mutual love and the exchange of mutual benefit are both beneficial and easy to practise in innumerable ways. I think it is only a matter of not having a ruler who delights in them, and that is all. If there was a ruler who delighted in these things, and encouraged people with rewards and praise, and intimidated them with penalties and punishments, I think the people would take to universal mutual love and interchange of mutual benefit just like fire goes up and water goes down and cannot be stopped in the world. [6]

Whether we think Mozi has it right, or whether we go with Confucius, between them, these two thinkers set out a tension that to this day is still hard to resolve. On the one hand, we are partial beings, evolved to live in small social groups where we love and care deeply for our intimates. But on the other hand, we are members of larger-scale societies where the needs of others conflict with our own partial caring.

How do we take into account the needs of others, many of whom we might never meet? Whom should we love? Why and how should we care? And what role should law have in making sure that we care?

Questions

- If somebody close to you, or somebody you loved, had committed a serious crime, what would you do? Would you report them, or would you try to remonstrate with them? And what do you think the right thing to do would be?

- Now think about the same question, but with a minor transgression (like stealing a chocolate bar). How do your answers change?

- And another question following on from the last two: where is the boundary, if any, between transgressions where you would favour interpersonal affiliation and love over broader concerns with justice?

- What is a more plausible basis for a well-ordered society: the model given by Confucius of graded concern, or the model given by Mozi of universal love? Why do you think this?

- Are the two models necessarily opposed to each other? Or can you find a way to harmonise them?

Notes

[1] Euthyphro 4c, in John M. Cooper (editor), Plato: Complete works (Hackett 1997), p. 4.

[2] Edward Slingerland (translator), Confucius: Analects (Hackett 2003), p. 124.

[3] From the Kongzi Jiayu 9:57, quoted in Huang Yong, “Why an Upright Son Does Not Disclose His Father Stealing a Sheep: A Neglected Aspect of the Confucian Conception of Filial Piety” in Asian Studies (XXI), 1 (2007), pp. 15-45.

[4] Ian Johnston (translator) The Mozi: A Complete Translation (Chinese University of Hong Kong Press 2010), p. 131-3.

[5] Edward Slingerland (translator), Confucius: Analects (Hackett 2003), p. 27.

[6] Ian Johnston (translator) The Mozi: A Complete Translation (Chinese University of Hong Kong Press 2010), pp. 163-165

Further Reading

Books and music

An excellent introduction to these ideas is Michael Puett and Christine Gross-Loh’s The Path: What Chinese Philosophers Can Teach Us About the Good Life ( Penguin 2017).

This week’s song is Paul Simon’s Something So Right.

Online

Several scholars have discussed anarchism in ancient Chinese thought, although usually in reference to Daoist traditions. For an overview, with some intriguing thoughts on the Confucians as well, try this article.

Image: The Triumph of Love, illustrating Francesco da Barberino’s Tractatus de Amore c. 1315. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.