Philosophers Behaving Badly?

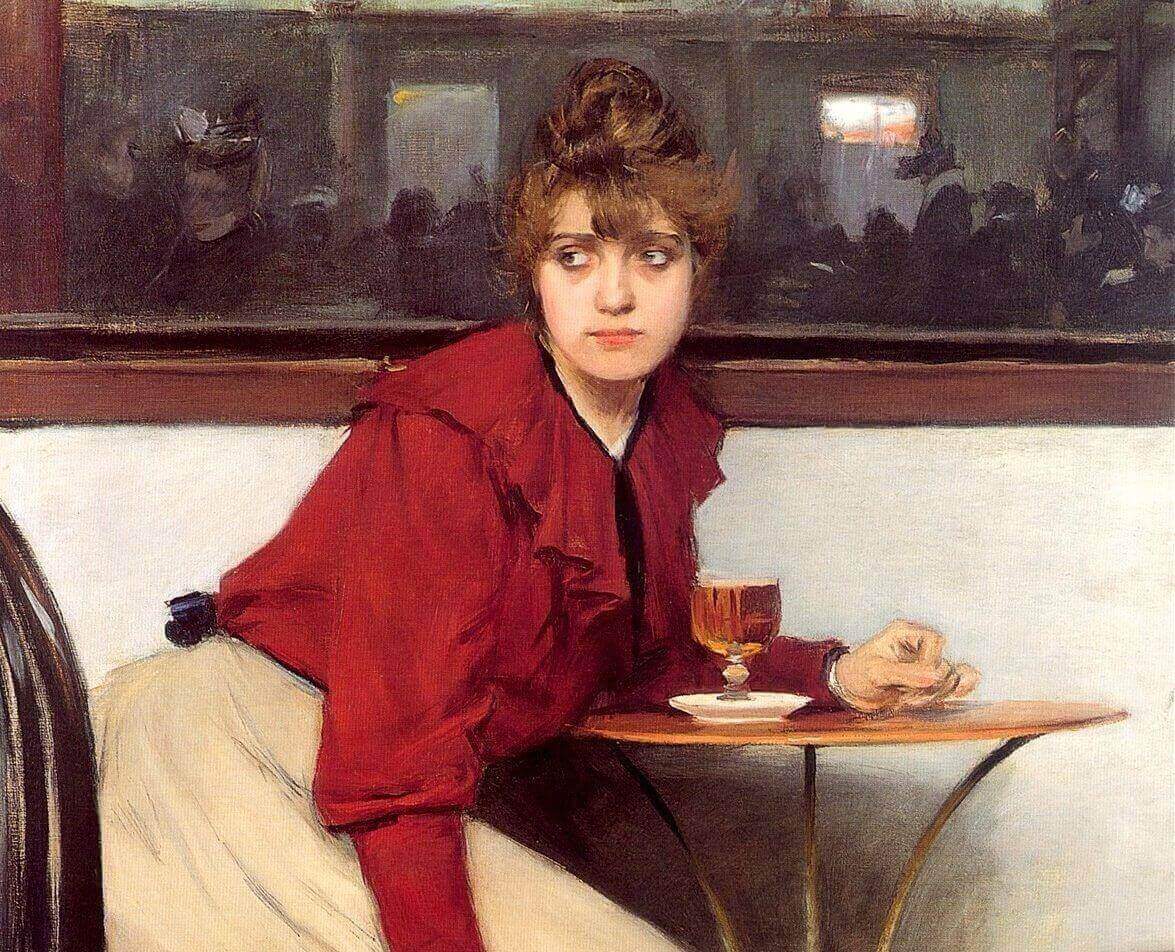

The philosopher Simone de Beauvoir was a big fan of philosophising while drunk. Along with her sidekick Jean Paul Sartre, De Beauvoir partied hard, with the full commitment you might expect given her existentialist tendencies. In this, she was part of a long tradition of philosophers who drink. This tradition is so well established that the bar-room philosopher has become a stock figure in popular mythology: the drunken rambler who lists across the room and corners you for a conversation about how you can be certain that the tables and chairs in the bar really exist.

But for all those philosophers who are partial to a tipple, others are more uneasy with drunkenness. Immanuel Kant — who in his younger days was known to drink so much he couldn’t find his way home — argued that drinking to excess makes human beings little better than animals, although he permitted mild inebriation for the sake of warmer social connections (what constitutes “mild”, of course, is a matter of fine judgement). And Socrates managed to somehow get the best of both worlds. He was the most sober of drunks, who could drink everybody under the table, without ever showing signs of loss of control.

So when you are next inclined towards philosophy, should you crack open a can of beer, an amphora of wine, or a cask of whiskey? Or should you abstain? Fortunately, Plato is here to guide you through the issues involved.

Drinking to Get Drunk With the Greek Philosophers

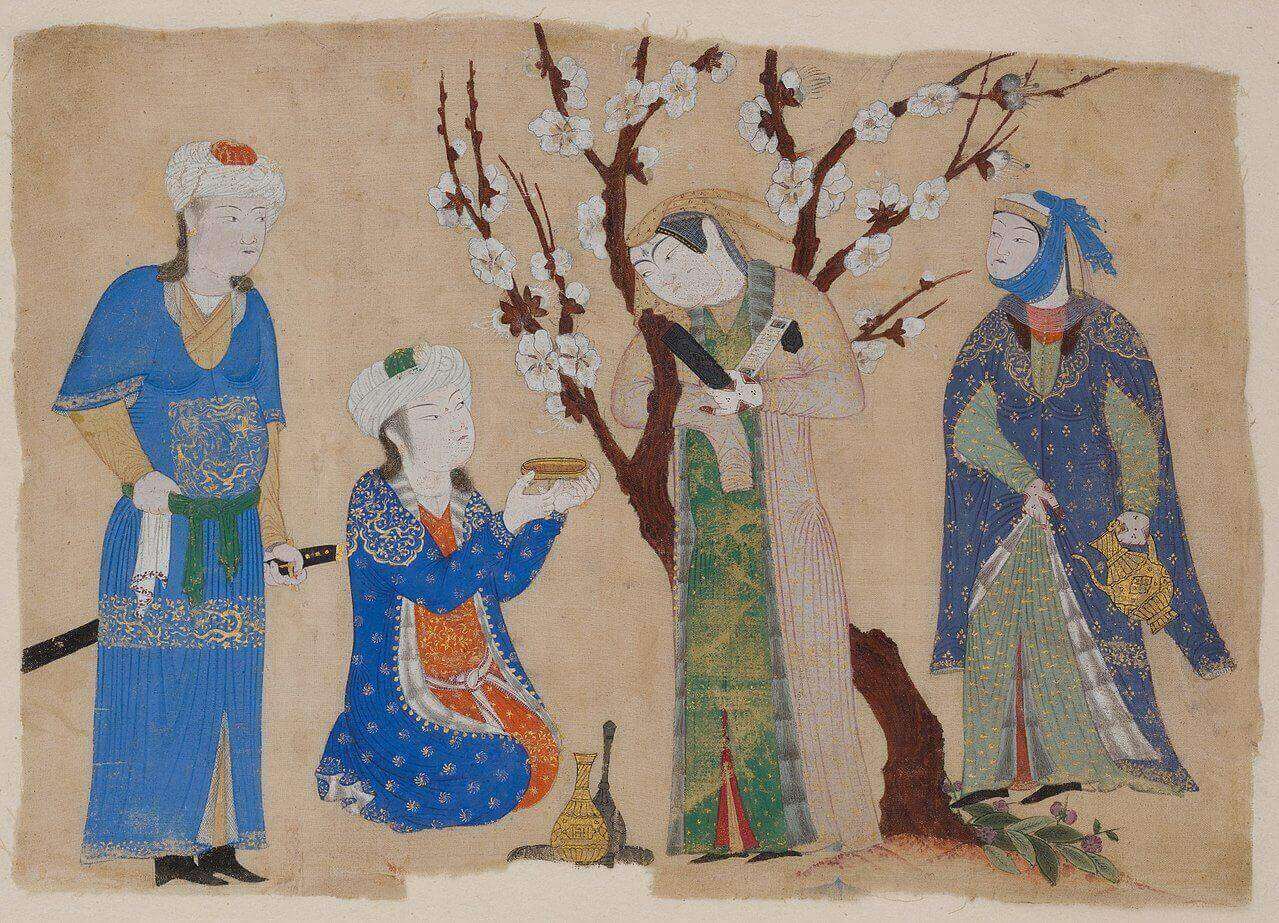

In Ancient Greece, one of the main places where philosophy took place was at symposia. These were drinking parties where (almost exclusively male, although see this excellent attempt at gatecrashing from the philosopher Hipparchia) philosophers hung out and talked a combination of sense and nonsense into the early hours. As Plato put it, passing time in conversation and drinking (as long as we conduct ourselves well) is a considerable contribution to education. How so? Because, as Sarah Mattice put it in her paper on drinking to get drunk in Greece and China, symposia were a form of training in controlled excess.

This is how Mattice describes a typical symposium, or philosophical drinking party.

In ancient Greece, symposia were a form of social gathering, centering on drinking wine, giving speeches, and playing various kinds of games. Although flute-girls and serving girls might be present for some of the evening, the participants were traditionally male citizens or men of equal status. The men would lounge on couches placed in a square, around which the wine mixture was passed in a ritual fashion. The symposiarch, or leader of the symposium, was responsible for mixing the wine to determine its strength and deciding on the topic of conversation. [1]

Guests at the symposium would take turns making speeches, singing songs, bragging, or philosophising out loud. And when the evening was done, they’d sometimes spill out into the street in a komos, or a drunken riot.

Drunkenness and the Law

But what good, philosophical reasons might there be for this behaviour? To answer this, we can turn to Plato’s Laws, his longest, and perhaps least-loved book. The Laws is a somewhat rambling account of a conversation that takes place in Crete. The three participants in the conversation are a stranger from Athens (known only as “the Athenian”), a Spartan called Megillus, and a Cretan called Kleinias.

The three men are talking about how to establish laws that can govern a new state called Magnesia. You might think a discussion of law would begin by asking about law itself, about what law is, or what makes something lawful. But instead, the very first book of the Laws launches into a discussion of drunkenness.

Why start in such an odd place? Plato makes clear that this choice of starting point is not arbitrary. Instead, the question of drunkenness and how to manage it is vital to thinking through what civilisation and law are about.

So let’s speak at greater length about the whole subject of intoxication. It is not a practice of minor significance, and to understand it is not the part of any paltry lawgiver. I’m speaking now, not about the drinking or non- drinking of wine in general, but about getting drunk. (Laws 637d) [2]

Why is drunkenness such a big deal? In part, it is because it brings to light the unruliness of human passion. And this unruliness is one of the biggest issues when it comes to establishing some kind of law or common measure in society.

Giddy Goats

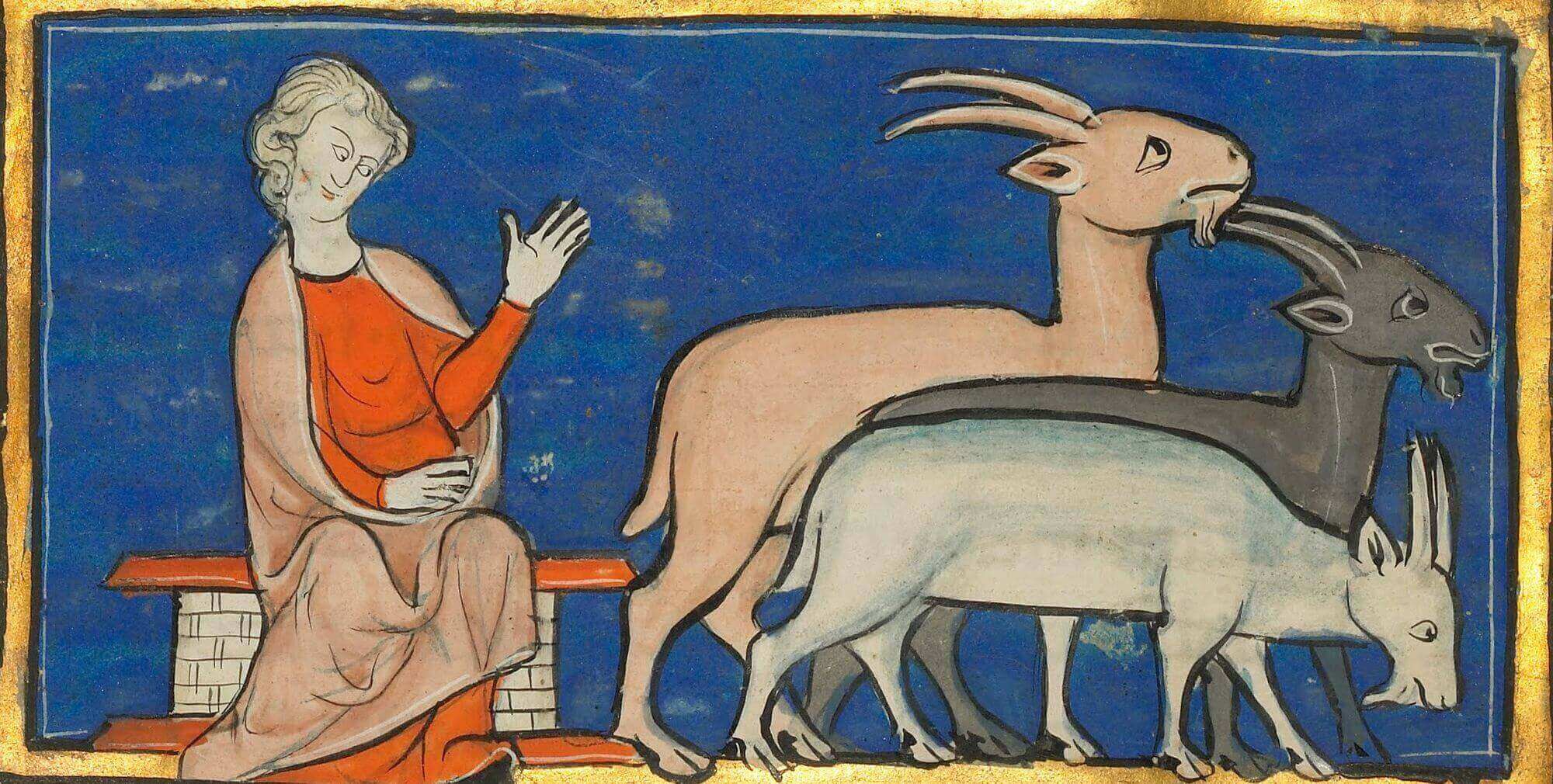

In the face of this unruliness, it might be tempting to abolish drunkenness altogether. This is what the austere Spartan Megillus recommends. But Plato thinks we should take more seriously the up-sides of drunkenness, and we should find ways of permitting a controlled unruliness for the greater social good. And his argument proceeds by means of an analogy with goats.

Imagine, the Athenian stranger in the Laws says, that somebody sees a herd of well-governed goats. Seeing how orderly the goats are, this person decides that goats in general are admirable beasts, and that raising goats is an excellent pursuit. Now imagine somebody else sees another herd of goats, but this second herd is not under the government of a good goat-herd. Unsurprisingly, this second person decides that goats are agents of chaos, worthy of our highest disdain.

Now imagine these two goat-observers falling into conversation. They start discussing the merits or demerits of goats, and they cannot agree. But what Plato wants us to see is that the issue is not really whether goats are good or bad. A goat is a goat is a goat: it is simply a thing in the world that requires careful management. So rather than thinking about whether we should praise or blame goats, invite them into our lives or abolish them, Plato wants us to think instead about how goats are governed.

So it is with the question of drunkenness. For Plato, what is at issue is not whether drunkenness is good or bad in itself. Instead, the issue is how we govern and manage it. And here, it becomes clear that the problems and opportunities presented by drunkenness have a common source: the fact that drunkenness amplifies everything. Drunkenness is an emotional megaphone.

In the Laws, Plato asks, “Doesn’t the drinking of wine make pleasures, pains, the spirited emotions, and the erotic emotions, more intense?” (Laws 645d). And because of this heightening of the emotions, drunkenness often diminishes our capacity for prudence (Laws 645d-e). It makes people such as magistrates, pilots and judges incompetent in the performance of their duties (Laws 674b). Plato even goes so far as to worry that drunken procreative sex (when the drinker is “raging with frenzy in body and soul”) is liable to lead to unfortunate, malformed, or ethically defective offspring (Laws 775 c-d).

But before we abolish drunkenness altogether, like the Spartan Megillus, Plato argues that drinking to excess also has its benefits, if it is managed properly. Well-governed drunkenness can increase social bonds (Laws 671e), it can heal the austerity of old age (Laws 666b), and it can make the soul softer, more pliable, leading to the possibility of its rejuvenation (Laws 666c).

Herding Goats and Philosophers

So when is it good to be drunk, and when is it not? Under what circumstances can drinking help you become a better philosopher, or a wiser human?

Plato recognises that while drunk, drinkers are at risk of all kinds of ignobility, brashness and rudeness. But if, like those rowdy goats, the drunk can be managed by a good goat-herd, a lawgiver, then their dispositions can be better shaped and transformed. After all, when it comes to philosophy, having a pliable, malleable soul can be of some benefit. When drunk, the soul is made soft. This makes it amenable to being better shaped and moulded into new forms, just as warmed or molten metal can be shaped by a skilled metalsmith.

Drinking, if done under the guidance of the sober and the wise, is like an alchemical laboratory for the human soul. It gives us the opportunity to get to grips with our emotions, our impulses, our pleasures and pains in raw form. And it allows us to develop greater self-control, as we wrestle these intense emotions into shape. As Sarah Mattice puts it:

With a sober symposiarch in the lead—monitoring the character of those involved—citizens are given the opportunity to test themselves against the desire to succumb to pleasures, at the very point when their self-control is at its lowest. By drinking wine and being present in a situation where shamelessness has a tendency to reign, the citizens can develop a resistance to immoderate behavior, and so develop their character. In addition, because for the Athenian, symposia would be civic events, they also provide the opportunity for the citizens’ virtue to be observed and tested. [3]

Doing Philosophy While Drunk

Good drunkenness, then, brings the passions to the surface. It allows us to connect with each other more deeply, more fiercely, and more fully. And if it is conducted under the auspices of a good guide, it is an education in combatting shamelessness, and in cultivating a proper sense of shame.

Here, it is clear why Socrates is the perfect symposiarch: he can match everyone drink for drink, but he never loses his head. He can benefit from the benefits that drunkenness brings, the social heat that is cooked up by drinking together, but he doesn’t suffer from any of the down-sides. He is convivial but self-controlled.

So should you do philosophy while drunk? What benefits might this bring? And under what circumstances should you engage in unsober philosophy? If Plato is right (and Kant too, and also De Beauvoir), then a slug of whiskey or a carafe of wine might help in the collective pursuit of philosophy.

But here, it might be worth being cautious. This series, after all, is on reading philosophy, and not just on doing philosophy. So what about the solitary philosopher/drinker? Here, Plato would encourage caution. After all, as philosopher Edward Slingerland points out in his book Drunk: How We Sipped, Danced, and Stumbled Our Way to Civilisation:

in most societies and for most of human history, the consumption of chemical intoxicants, especially alcohol, has been a fundamentally social act. In the vast majority of societies, no one drinks alone. [4]

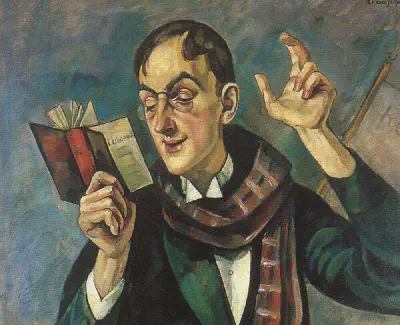

So here the advice might be this: philosophise when drunk by all means. But if you want to derive benefit from drunken philosophy, you need to engage in it alongside others. Instead of reading in solitary silence, try reading your philosophy out loud, in the company of others, with a lot of riotous joking and discussion and banter, and see what benefits this brings to your reading, and to your life as a philosopher.

However, here we need to ask one final question: what if you don’t drink? What about all those teetotal philosophers out there? Are you doomed to missing out/ Not necessarily! Because if what is most important here is the sense of boldness, the vivacity of emotion, what Plato might call the softness of the soul, and the sheer joy of being with others, then alcohol is not the end but a means. What matters most for doing philosophy, in this view, is conviviality, however you choose to cultivate it.

So this will be the topic of the next piece in this series: because for Plato, philosophy, like drinking, is a communal pursuit.

Read the whole series on seven ways of reading philosophy…

- Reading Napoleonically

- Reading haphazardly

- Reading self-interestedly

- Reading out loud

- Reading drunkenly

- Reading for laughs

- Reading with others (forthcoming!)

Notes

[1] Sarah Mattice (2011). Drinking to Get Drunk: Pleasure, Creativity, and Social Harmony in Greece and China. Comparative and Continental Philosophy, 3(2), 243-253.

[2] All quotations of Plato’s Laws are from Thomas Pangle (1988), The Laws of Plato, Chicago University Press.

[3] Mattice, ibid.

[4] Edward Slingerland (2021), Drunk: How We Sipped, Danced, and Stumbled Our Way to Civilisation. Hachette. EPUB edition.

Further Reading

See Skye Cleary’s terrific article Being and drunkenness: how to party like an existentialist in Aeon Magazine.